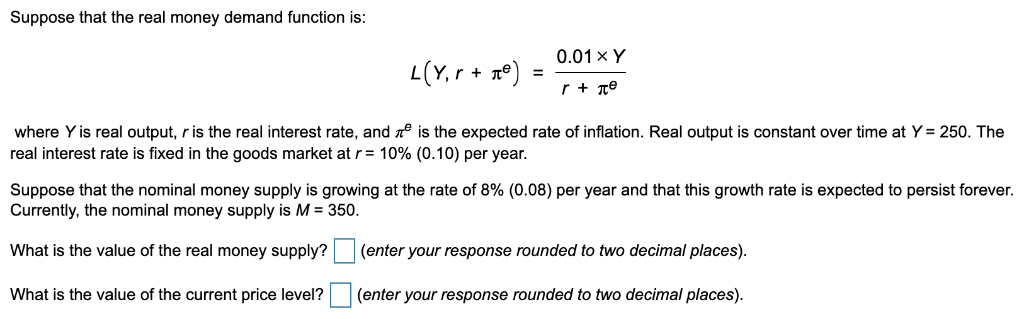

Money Demand Real Interest Rate

Let us make an in-depth study of the linking variables between interest rate and income.

- Aggregate Demand Interest Rates

- Money Demand Real Interest Rate Equation

- Money Demand Real Interest Rates

- Money Demand And Real Interest Rate

- Interest Demand Curve

They are: price level, real income, rate of interest and rate of increase in the price level. Friedman’s quantity theory of money can be explained diagrammatically in the following figure (fig.2) In the figure while the X-axis shows the demand and supply of money, Y-axis measures the income level. Real money demand and the real money supply as functions of the real interest rate are illustrated in the above graph. Real money demand is graphed holding fixed real income and expected inflation. The real money supply is equal to the nominal amount of M1, denoted M 0, divided by the fixed aggregate price level, P 0. It is assumed that the Fed does not alter the money supply based on the valued of the real interest rate. Growth in real output (i.e., real GDP) will increase the demand for money and will increase the nominal interest rate if the money supply is held constant. On the other hand, if the supply of money increases in tandem with the demand for money, the Fed can help to stabilize nominal interest rates and related quantities (including inflation).

Introduction:

The interest rate and income are linking variables transmitting changes from the monetary sector to the goods sector and from the goods sector to the money sector. We now examine this relationship in more detail and analyse the concept of general equilibrium in the whole economy, consisting of the goods and money sectors.

Fig. 6.1 is a summary of equilibrium in the two sectors. The IS and LM curves represent the conditions that have to be satisfied in order for the goods and money sectors, respectively, to be in equilibrium. Now our task is to determine how these markets are brought into simultaneous equilibrium. For simultaneous equilibrium, interest rates and income levels have to be such that both goods market and money market are in equilibrium.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

That condition is satisfied at the point E in Fig. 6.1 which is the point of general equilibrium. This occurs at one combination of real income and the interest rate re and Ye and with this combination of income and interest rate there is no tendency for anything to change; individuals are in equilibrium in their allocation of wealth among different assets, and in their allocation of output among different uses.

Even though we are not concerned with the problem of economic dynamics, it is nevertheless important to understand the economic forces generated in this equilibrium, which tend to bring the system back to equilibrium.

Fig. 6.2(b) represents the equilibrium conditions for the goods and money sectors. Fig. 6.2(c) shows the money sector from which the LM curve in Fig.6.2(b) is derived and Fig 6.2(a) shows the desired investment schedule which together with the consumption function (not shown here) was used to derive the IS curve in Fig 6.2(b).

Point A shows the combination of real income (Y2) and interest rate (re) , respectively, which represents general equilibrium for the economy. At point A in the money sector, the quantity of money demanded shown by the demand curve Y2 is equal to the quantity of money supplied. At the interest rate re, desired investment is equal to IA – this is shown in Fig. 6.2(a). As point A is on the IS curve, we know that saving generated by a real income of Y2 is equal to IA, because every point on the IS curve represents a situation in which saving is equal to desired investment.

Let us consider point B in Fig. 6.2(b) which shows the combination of real income and interest rate Y2 and rB, respectively. We want to know what forces will be generated when the economy found itself in the situation represented by point B, and how these forces will work to bring the economy back to equilibrium. We know that at point B neither the goods nor the money sector is in equilibrium, because point B, is off both the IS and LM curves. Thus, something will have to change in both sectors.

In the money sector 6.2(c), we can see that at the combination of income and interest rate represented by point B, the quantity of money demanded is less than the quantity of money supplied. Individuals will try to re-allocate their wealth from money to bonds, thus pushing interest rate down. The arrow pointing down at B represents this tendency.

At panel 6.2(a), we see that at the interest rate rB, desired investment is IB. However, at real income Y2, saving is equal to IA, because we assume that S is a function of real income only; thus at point B, S > IB. Hence in the goods sector, point B represents a situation in which AD < Y. Given our present assumption about the effects of a disequilibrium in the goods sector, S > (desired) I will tend to reduce output (real income).

The arrow pointing to the left at B represents this tendency. (According to our assumptions about the goods sector disequilibrium, this only affects output, not the price level and as such it does not affect the LM curve).

The initial forces generated in disequilibrium have further repercussions on the whole economic system. The fall in the interest rate generated by excess supply of money will affect desired I =f(r). The fall in real income F generated by S > I (desired) in the goods sector will affect the demand for money, which is a function of real Y only. As the interest rate falls, desired I rises, reducing S > I (desired). As real Y falls, the demand for money and the interest rate fall, strengthening the effects mentioned above. All of this will continue until point A is reached — equilibrium point, in Fig. 6.2.

Disequilibrium and Dynamics in the Goods and Money Market:

Equilibrium is said to be a stable one when economic forces tend to push the market towards it. Fig. 6.3 shows that the general equilibrium described here is indeed a stable one. To show this, we consider all the points to the left of the IS curve, like point A where interest rate r1 and the level of Y1 are too low for equilibrium to be achieved in the real sector. This means that the total value of output is less than the demand.

In this situation, businesses find their inventories run down involuntarily and so act to increase output which pushes up Y. For all points to the left of the IS curve, there is an excess demand for goods and thus there is pressure on income to rise. Similarly, tor all points to the right of the IS curve, there is excess supply of goods and there is pressure on Y to fall.

Now we consider points above the LM curve, like point B. At this point, with the level of Y, OY1, the interest rate is too high for money market equilibrium to be achieved. This means that the supply of money exceeds the demand for money and so downward pressure is exerted on the interest rate. This is true for all points above the LM curve, as shown in Fig. 6.3 and it is also true that upward pressure will be exerted on interest rates at all points below the LM curve as there is excess demand for money.

The direction of the pressure being exerted on incomes and interest rates in the four quadrants are indicated by arrows in Fig. 6.3. At any disequilibrium point, such as C, economic forces will be pushing the market towards the general equilibrium position.

Shifting the IS and LM Curves:

Having analysed equilibrium in the two sectors, it is useful to examine how changes in behaviour will affect the two variables in which we are interested at present — real income and interest rate. There are four behavioural functions that determine equilibrium in the two sectors – the investment function and consumption function and the supply of money function and the demand for money function.

These functions were used to derive the IS and the LM curves and thus the behaviour represented by these functions is held constant along the IS and LM curves. A change is behaviour can be represented by a shift in these functions. Such shifts will result in the shift of the IS or LM curves, or, both.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Let us start from a situation of general equilibrium as shown by point A in Fig. 6.4. This is an equilibrium for that set of behavioural functions which underlies the derivation of the IS and LM curves intersecting at A. We now assume that for some reason, desired expenditures increase. For example, suppose there is an increase in desired investment at all interest rates (a shift in the investment function) or a rise in desired consumption at all income levels (a shift in the consumption function). These changes can be represented by a shift of the IS curve from IS to I’S’.

Now the economy is no longer in equilibrium at A because the goods sector now represented by I’S’ is no longer in equilibrium. However, the money sector is still in equilibrium as there is no change in the behaviour of the functions which affect money sector. We know that with the new IS curve, point A represents a situation in which desired expenditures are greater than total output (or I > S ). This will lead to an increase in Y.

As real Y rises, point A no longer represents equilibrium in the money sector either, because the increase in real Y affects the quantity of money demanded and thus equilibrium in the money sector will also change, though has been no behavioural change in the money sector (and hence the LM curve does not shift; there is a movement along the curve). The rise in the interest rate will’ have effects on desired I and on real Y.

This process will continue until a new equilibrium is reached at B with interest rate at rB and real income at YB. At B, both the money and goods sectors are in equilibrium. It may be pointed out here that if the shift in desired expenditures or AD had not affected the interest rate, real income would have changed from YA to Yc, which is equal to the initial change ‘in AD x the multiplier. This would be true if the LM curve is horizontal. Real Y only rises to YB because some of the initial increase in AD is offset by the effect of the rise in the interest rate on desired I, called the ‘crowding-out effect’.

A shift of the LM curve can occur because of a change in the demand for money or in the supply of money. An increase in the supply of money or a decrease in the demand for money can be represented by a shift of the LM curve to the right. To examine the effect of such changes, let us again start from a position of equilibrium at point A in Fig. 6.5. Assume there is an increase in the supply of money brought about by an open-market operation by the monetary authority. With the new money supply, equilibrium in the money sector can be represented by L’M’ curve in Fig. 6.5.

At A, the goods sector is still in equilibrium, since nothing has happened to change the IS curve. However at A, the quantity of money supplied is greater than the quantity of money demanded as the situation in the money sector represented by the L’M’ curve. Individuals will be attempting to reallocate their wealth from money into bonds, thus driving the interest down.

The fall in interest rate also affects the goods sector via its effect on desired I; thus point A will not remain an equilibrium point for the goods sector either. The changes in the goods sector thus generated will have repercussions on the money sector. The process will continue until a new equilibrium is reached at point B, at which both sectors are in equilibrium again.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The above discussion shows how changes in one sector of the economy are transmitted to the other sectors, and how the final equilibrium of the whole system is reached. It is obvious that changes occurring in one sector can only be transmitted to another sector if there exist variables linking the two sectors, and if these changes affect these linking variables.

In our model, the linking variables are the interest rate and real Y. The interest rate is an effective linking variable, transmitting changes of behaviour occurring in the money sector to the goods sector, because the change in the money sector had an effect on the interest rate and the interest rate enters in the goods sector through investment decisions.

Real Y is an effective linking variable, transmitting changes of behaviour in the goods sector to the money sector, because changes of behaviour in the goods sector has an effect on real income Y and real Y enters into decision in the money sector through changes in the demand for money.

To get a better idea about these linking variables, we examine the following cases:

i. The Perfectly Elastic Demand for Money or the Liquidity Trap:

We have already seen the interest rate as a measure of the alternative cost of holding wealth in the form of money rather than in the form of other assets and thus, as a measure of the cost of acquiring the services yielded by money. When the interest rate is zero, the cost of acquiring services provided by money is zero and people will be willing to hold all their wealth in the form of money rather than other assets.

It is possible that even when the interest rate is positive, the expected cost of holding wealth in the form of money is zero. We have already seen that one of the costs of holding bonds is the risk of capital loss arising from a change in the interest rate. When the interest rate rises, there would be a fall in the capital value of bonds; the expected return from holding a bond is equal to the interest yield minus the expected capital toss. If these two are equal, the expected final return is still zero, even though the interest yield is positive.

Assume for the moment that the interest rate is considered to be normal, say, rn. If the interest rate falls below rn , individuals expect it to return to rn and thus they expect to suffer a capital loss if they hold bonds. Let rL < rn be the interest rate which would cause capital loss if the interest rate rises from r, to the expected rate rn which exactly offsets the return represented by rL.

In this case, at the interest rate rL, the expected return from holding a bond is zero. At the interest rate above rL, it is positive, and at an interest rate below rL, it is negative. This case is represented by a demand curve for money which becomes perfectly elastic at the interest rate rL in Fig. 6.6.

Fig. 6.6 (a) shows 3 demand curves for money for three different incomes, where Y1 < Y2 < Y3, having the property that at the interest rate rL they become perfectly elastic — at this interest rate people are willing to hold all their wealth in the form of money. Ms1 and Ms2 are two different supply curves of money. In Fig. 6.6 (b), the LM curves are derived to represent this situation. They are perfectly elastic at the interest rate rL for incomes up to Y2 for LM1 and up to Y3 for LM2.

The increase in money supply from Ms1 to MS2 only affects the elastic part of the LM curve, because an increase in the supply of money along the perfectly elastic part of the demand curve for money has no effect on the interest rate. Individuals are willing to hold more money, rather than bonds at rL, where the cost of holding money is zero and individuals are indifferent between money and bonds.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Fig. 6.7 represents a general equilibrium situation for a goods sector represented by IS curve and a money sector exhibiting the properties above, represented by LM, with equilibrium for both sectors on the horizontal part of the LM curve at Ye and rL, respectively. Assume there is an increase in the supply of money shown by a shift of the LM curve from LM1 to LM2. This has no effect on the equilibrium value of real Y or the interest rate because the part of the LM curve affected by this change is not relevant to the determination of equilibrium.

ii. The Supply of Money is Perfectly Elastic:

This happens when the monetary authority decides to fix the interest rate at some given level. To do this, they will have to supply whatever quantity of money is demanded at that rate, otherwise the interest rate would be affected by the excess demand or supply of money and would not be maintained at the desired level. This is shown in Fig. 6.8(a) which shows a supply curve that is perfectly elastic at the interest rate rf and three demand curves for three incomes. In Fig. 6.8(b), we derive the LM curve for this situation. It is perfectly elastic at the interest rate rf. We can see that any changes in the demand for money (or price level) will have no effect on the LM curve.

If we draw the IS curve on the LM curve of Fig. 6.8(b), we have the same general equilibrium situation as the one in Fig. 6.7. Again changes in the demand for money (or price level) will have no effect on equilibrium Y or interest rate. This is the situation which Keynes experienced and thus, he advocated fiscal policy as an effective instrument for influencing the economy.

iii. The Perfectly Inelastic Investment Function:

The IS curve represents all the combinations of income and interest rate at which AD = Total Output. Both the interest rate and real income are relevant here because we assume that both these variables affect decisions about AD; the interest rate affects desired investment and real income affects desired consumption.

If we now drop the assumption that desired investment depends on the interest rate, real Y becomes the only variable that affects AD, and the IS curve in such a situation will be perfectly inelastic. Fig. 6.9 shows such an IS curve with two LM curves representing two different conditions in the money sector (two different supply functions).

With both LM curves, general equilibrium in the two sectors occurs at the same real income but at different interest rates. Thus any changes in the money sector (shifts in the LM curve) only affect the interest rate, but leave real Y unchanged. However, changes in the goods sector (shift of the IS) affect both real Y and the interest rate.

iv. The Real Balance Effect:

The Neo-Classical economists, mainly Prof. Pigou, produced an argument against the Keynesian liquidity trap case in the shape of real balance effect. According to this, with a constant nominal money supply, a general deflation of wages and prices tend to increase the real value of people’s holdings of money above their desired levels.

Consequently, people will reduce their savings and increase their consumption in an attempt to reduce their real balances. In a situation of unemployment, as wages and prices fall and the LM curve shifts to the right, the IS curve will also shift to the right as consumption increases. With both curves now shifting to the right, the equilibrium levels of income and hence employment must increase (even in the liquidity trap and with interest-inelastic investment) and there is now nothing to stop full employment from being reached. This is illustrated in Fig. 6.10.

Theoretically, then, the neo-classical economists appear to have the stronger case. Only when it came to policy-making, did the Keynesians have the upper hand, given the recognised inflexibility of wages and prices downward.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The cases examined here are important in showing, how, by changing assumptions about behaviour; the inter-relationship between the two sectors is changed. In the first two cases, we still assume that there is a linking variable between the goods and money sectors; desired investment is assumed to be a function of the interest rate.

However, the assumptions about the money sector are such that any changes in this sector do not affect the linking variable (the interest rate) and thus such changes are not transmitted in the goods sector. In the case of the assumption about a perfectly inelastic investment function, the goods sector is totally independent of the money sector — no behaviour in the goods sector is affected by the money sector.

Even if changes in the money sector affect the interest rate, it is unlikely to affect the goods sector so long as the interest rate plays no role in any behaviour relevant to that sector. (If consumption is a function of interest rate, this would reintroduce a link between the goods and the money sectors even though desired investment is not a function of the interest rate). However, changes in the goods sector do affect the money sector, because the variable linking the two – real income — is effective as long as the demand for money is a function of real income which may change because of the real balance effective.

A Formal Treatment of the IS-LM Model:

Equilibrium Income and the Interest Rate:

Aggregate Demand Interest Rates

The intersection of the IS and LM curves determines equilibrium income and interest rate. We derive expressions for these values by using the equations of IS and LM curves.

Motives for Holding Money

In deciding how much money to hold, people make a choice about how to hold their wealth. How much wealth shall be held as money and how much as other assets? For a given amount of wealth, the answer to this question will depend on the relative costs and benefits of holding money versus other assets. The demand for money is the relationship between the quantity of money people want to hold and the factors that determine that quantity.

To simplify our analysis, we will assume there are only two ways to hold wealth: as money in a checking account, or as funds in a bond market mutual fund that purchases long-term bonds on behalf of its subscribers. A bond fund is not money. Some money deposits earn interest, but the return on these accounts is generally lower than what could be obtained in a bond fund. The advantage of checking accounts is that they are highly liquid and can thus be spent easily. We will think of the demand for money as a curve that represents the outcomes of choices between the greater liquidity of money deposits and the higher interest rates that can be earned by holding a bond fund. The difference between the interest rates paid on money deposits and the interest return available from bonds is the cost of holding money.

One reason people hold their assets as money is so that they can purchase goods and services. The money held for the purchase of goods and services may be for everyday transactions such as buying groceries or paying the rent, or it may be kept on hand for contingencies such as having the funds available to pay to have the car fixed or to pay for a trip to the doctor.

The transactions demand for money is money people hold to pay for goods and services they anticipate buying. When you carry money in your purse or wallet to buy a movie ticket or maintain a checking account balance so you can purchase groceries later in the month, you are holding the money as part of your transactions demand for money.

The money people hold for contingencies represents their precautionary demand for money. Money held for precautionary purposes may include checking account balances kept for possible home repairs or health-care needs. People do not know precisely when the need for such expenditures will occur, but they can prepare for them by holding money so that they’ll have it available when the need arises.

People also hold money for speculative purposes. Bond prices fluctuate constantly. As a result, holders of bonds not only earn interest but experience gains or losses in the value of their assets. Bondholders enjoy gains when bond prices rise and suffer losses when bond prices fall. Because of this, expectations play an important role as a determinant of the demand for bonds. Holding bonds is one alternative to holding money, so these same expectations can affect the demand for money.

John Maynard Keynes, who was an enormously successful speculator in bond markets himself, suggested that bondholders who anticipate a drop in bond prices will try to sell their bonds ahead of the price drop in order to avoid this loss in asset value. Selling a bond means converting it to money. Keynes referred to the speculative demand for money as the money held in response to concern that bond prices and the prices of other financial assets might change.

Of course, money is money. One cannot sort through someone’s checking account and locate which funds are held for transactions and which funds are there because the owner of the account is worried about a drop in bond prices or is taking a precaution. We distinguish money held for different motives in order to understand how the quantity of money demanded will be affected by a key determinant of the demand for money: the interest rate.

Interest Rates and the Demand for Money

The quantity of money people hold to pay for transactions and to satisfy precautionary and speculative demand is likely to vary with the interest rates they can earn from alternative assets such as bonds. When interest rates rise relative to the rates that can be earned on money deposits, people hold less money. When interest rates fall, people hold more money. The logic of these conclusions about the money people hold and interest rates depends on the people’s motives for holding money.

The quantity of money households want to hold varies according to their income and the interest rate; different average quantities of money held can satisfy their transactions and precautionary demands for money. To see why, suppose a household earns and spends $3,000 per month. It spends an equal amount of money each day. For a month with 30 days, that is $100 per day. One way the household could manage this spending would be to leave the money in a checking account, which we will assume pays zero interest. The household would thus have $3,000 in the checking account when the month begins, $2,900 at the end of the first day, $1,500 halfway through the month, and zero at the end of the last day of the month. Averaging the daily balances, we find that the quantity of money the household demands equals $1,500. This approach to money management, which we will call the “cash approach,” has the virtue of simplicity, but the household will earn no interest on its funds.

Consider an alternative money management approach that permits the same pattern of spending. At the beginning of the month, the household deposits $1,000 in its checking account and the other $2,000 in a bond fund. Assume the bond fund pays 1% interest per month, or an annual interest rate of 12.7%. After 10 days, the money in the checking account is exhausted, and the household withdraws another $1,000 from the bond fund for the next 10 days. On the 20th day, the final $1,000 from the bond fund goes into the checking account. With this strategy, the household has an average daily balance of $500, which is the quantity of money it demands. Let us call this money management strategy the “bond fund approach.”

Remember that both approaches allow the household to spend $3,000 per month, $100 per day. The cash approach requires a quantity of money demanded of $1,500, while the bond fund approach lowers this quantity to $500.

Bond Funds

The bond fund approach generates some interest income. The household has $1,000 in the fund for 10 days (1/3 of a month) and $1,000 for 20 days (2/3 of a month). With an interest rate of 1% per month, the household earns $10 in interest each month ([$1,000 × 0.01 × 1/3] + [$1,000 × 0.01 × 2/3]). The disadvantage of the bond fund, of course, is that it requires more attention—$1,000 must be transferred from the fund twice each month. There may also be fees associated with the transfers.

Of course, the bond fund strategy we have examined here is just one of many. The household could begin each month with $1,500 in the checking account and $1,500 in the bond fund, transferring $1,500 to the checking account midway through the month. This strategy requires one less transfer, but it also generates less interest—$7.50 (= $1,500 × 0.01 × 1/2). With this strategy, the household demands a quantity of money of $750. The household could also maintain a much smaller average quantity of money in its checking account and keep more in its bond fund. For simplicity, we can think of any strategy that involves transferring money in and out of a bond fund or another interest-earning asset as a bond fund strategy.

Which approach should the household use? That is a choice each household must make—it is a question of weighing the interest a bond fund strategy creates against the hassle and possible fees associated with the transfers it requires. Our example does not yield a clear-cut choice for any one household, but we can make some generalizations about its implications.

First, a household is more likely to adopt a bond fund strategy when the interest rate is higher. At low interest rates, a household does not sacrifice much income by pursuing the simpler cash strategy. As the interest rate rises, a bond fund strategy becomes more attractive. That means that the higher the interest rate, the lower the quantity of money demanded.

Second, people are more likely to use a bond fund strategy when the cost of transferring funds is lower. The creation of savings plans, which began in the 1970s and 1980s, that allowed easy transfer of funds between interest-earning assets and checkable deposits tended to reduce the demand for money.

Some money deposits, such as savings accounts and money market deposit accounts, pay interest. In evaluating the choice between holding assets as some form of money or in other forms such as bonds, households will look at the differential between what those funds pay and what they could earn in the bond market. A higher interest rate in the bond market is likely to increase this differential; a lower interest rate will reduce it. An increase in the spread between rates on money deposits and the interest rate in the bond market reduces the quantity of money demanded; a reduction in the spread increases the quantity of money demanded.

Firms, too, must determine how to manage their earnings and expenditures. However, instead of worrying about $3,000 per month, even a relatively small firm may be concerned about $3,000,000 per month. Rather than facing the difference of $10 versus $7.50 in interest earnings used in our household example, this small firm would face a difference of $2,500 per month ($10,000 versus $7,500). For very large firms such as Toyota or AT&T, interest rate differentials among various forms of holding their financial assets translate into millions of dollars per day.

How is the speculative demand for money related to interest rates? When financial investors believe that the prices of bonds and other assets will fall, their speculative demand for money goes up. The speculative demand for money thus depends on expectations about future changes in asset prices. Will this demand also be affected by present interest rates?

If interest rates are low, bond prices are high. It seems likely that if bond prices are high, financial investors will become concerned that bond prices might fall. That suggests that high bond prices—low interest rates—would increase the quantity of money held for speculative purposes. Conversely, if bond prices are already relatively low, it is likely that fewer financial investors will expect them to fall still further. They will hold smaller speculative balances. Economists thus expect that the quantity of money demanded for speculative reasons will vary negatively with the interest rate.

The Demand Curve for Money

We have seen that the transactions, precautionary, and speculative demands for money vary negatively with the interest rate. Putting those three sources of demand together, we can draw a demand curve for money to show how the interest rate affects the total quantity of money people hold. The demand curve for money shows the quantity of money demanded at each interest rate, all other things unchanged. Such a curve is shown in Figure 10.7 “The Demand Curve for Money.” An increase in the interest rate reduces the quantity of money demanded. A reduction in the interest rate increases the quantity of money demanded.

Figure 10.7. The Demand Curve for Money. The demand curve for money shows the quantity of money demanded at each interest rate. Its downward slope expresses the negative relationship between the quantity of money demanded and the interest rate.

The relationship between interest rates and the quantity of money demanded is an application of the law of demand. If we think of the alternative to holding money as holding bonds, then the interest rate—or the differential between the interest rate in the bond market and the interest paid on money deposits—represents the price of holding money. As is the case with all goods and services, an increase in price reduces the quantity demanded.

Other Determinants of the Demand for Money

We draw the demand curve for money to show the quantity of money people will hold at each interest rate, all other determinants of money demand unchanged. A change in those “other determinants” will shift the demand for money. Among the most important variables that can shift the demand for money are the level of income and real GDP, the price level, expectations, transfer costs, and preferences.

Money Demand Real Interest Rate Equation

Real GDP

Money Demand Real Interest Rates

A household with an income of $10,000 per month is likely to demand a larger quantity of money than a household with an income of $1,000 per month. That relationship suggests that money is a normal good: as income increases, people demand more money at each interest rate, and as income falls, they demand less.

An increase in real GDP increases incomes throughout the economy. The demand for money in the economy is therefore likely to be greater when real GDP is greater.

The Price Level

The higher the price level, the more money is required to purchase a given quantity of goods and services. All other things unchanged, the higher the price level, the greater the demand for money.

Expectations

The speculative demand for money is based on expectations about bond prices. All other things unchanged, if people expect bond prices to fall, they will increase their demand for money. If they expect bond prices to rise, they will reduce their demand for money.

The expectation that bond prices are about to change actually causes bond prices to change. If people expect bond prices to fall, for example, they will sell their bonds, exchanging them for money. That will shift the supply curve for bonds to the right, thus lowering their price. The importance of expectations in moving markets can lead to a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Expectations about future price levels also affect the demand for money. The expectation of a higher price level means that people expect the money they are holding to fall in value. Given that expectation, they are likely to hold less of it in anticipation of a jump in prices.

Expectations about future price levels play a particularly important role during periods of hyperinflation. If prices rise very rapidly and people expect them to continue rising, people are likely to try to reduce the amount of money they hold, knowing that it will fall in value as it sits in their wallets or their bank accounts. Toward the end of the great German hyperinflation of the early 1920s, prices were doubling as often as three times a day. Under those circumstances, people tried not to hold money even for a few minutes—within the space of eight hours money would lose half its value!

Transfer Costs

For a given level of expenditures, reducing the quantity of money demanded requires more frequent transfers between nonmoney and money deposits. As the cost of such transfers rises, some consumers will choose to make fewer of them. They will therefore increase the quantity of money they demand. In general, the demand for money will increase as it becomes more expensive to transfer between money and nonmoney accounts. The demand for money will fall if transfer costs decline. In recent years, transfer costs have fallen, leading to a decrease in money demand.

Preferences

Preferences also play a role in determining the demand for money. Some people place a high value on having a considerable amount of money on hand. For others, this may not be important.

Money Demand And Real Interest Rate

Household attitudes toward risk are another aspect of preferences that affect money demand. As we have seen, bonds pay higher interest rates than money deposits, but holding bonds entails a risk that bond prices might fall. There is also a chance that the issuer of a bond will default, that is, will not pay the amount specified on the bond to bondholders; indeed, bond issuers may end up paying nothing at all. A money deposit, such as a savings deposit, might earn a lower yield, but it is a safe yield. People’s attitudes about the trade-off between risk and yields affect the degree to which they hold their wealth as money. Heightened concerns about risk in the last half of 2008 led many households to increase their demand for money.

Figure 10.8 “An Increase in Money Demand” shows an increase in the demand for money. Such an increase could result from a higher real GDP, a higher price level, a change in expectations, an increase in transfer costs, or a change in preferences.

Figure 10.8. An Increase in Money Demand. An increase in real GDP, the price level, or transfer costs, for example, will increase the quantity of money demanded at any interest rate r, increasing the demand for money from D1 to D2. The quantity of money demanded at interest rate r rises from M to M′. The reverse of any such events would reduce the quantity of money demanded at every interest rate, shifting the demand curve to the left.

Self Check: Demand for Money

Interest Demand Curve

Answer the question(s) below to see how well you understand the topics covered in the previous section. This short quiz does not count toward your grade in the class, and you can retake it an unlimited number of times.

You’ll have more success on the Self Check if you’ve completed the Reading in this section.

Use this quiz to check your understanding and decide whether to (1) study the previous section further or (2) move on to the next section.